אלכסנדר טבצ'ניק

מלגאי של קתדרת חייקין לגאואסטרטגיה

Russia’s involvement in the Persian Gulf

Alexander Tabachnik

Russia is positioning itself as a rising military and political power, one of the world’s major power centers, while staking a claim on widening its spheres of influence, including in the Middle East and particularly in the Persian Gulf. By a relatively successful intervention in Syria, Russia has confirmed its determination to strengthen its position in the Middle East, while demonstrating determination to support its allies and ability to reach the defined goals to a large extent.[1] Furthermore, Russia seeks to present itself as a pragmatic, nonideological and reliable partner with a capability of resolving regional conflicts by both diplomatic and military means.[2]

Thus, what goals does Russia pursue when it strives to strengthen its positions in the Persian Gulf, considering the fact that this region cannot be defined as Russia’s traditional sphere of influence?

It can be argued that by its involvement in the region of the Gulf, Russia pursues the four major goals.

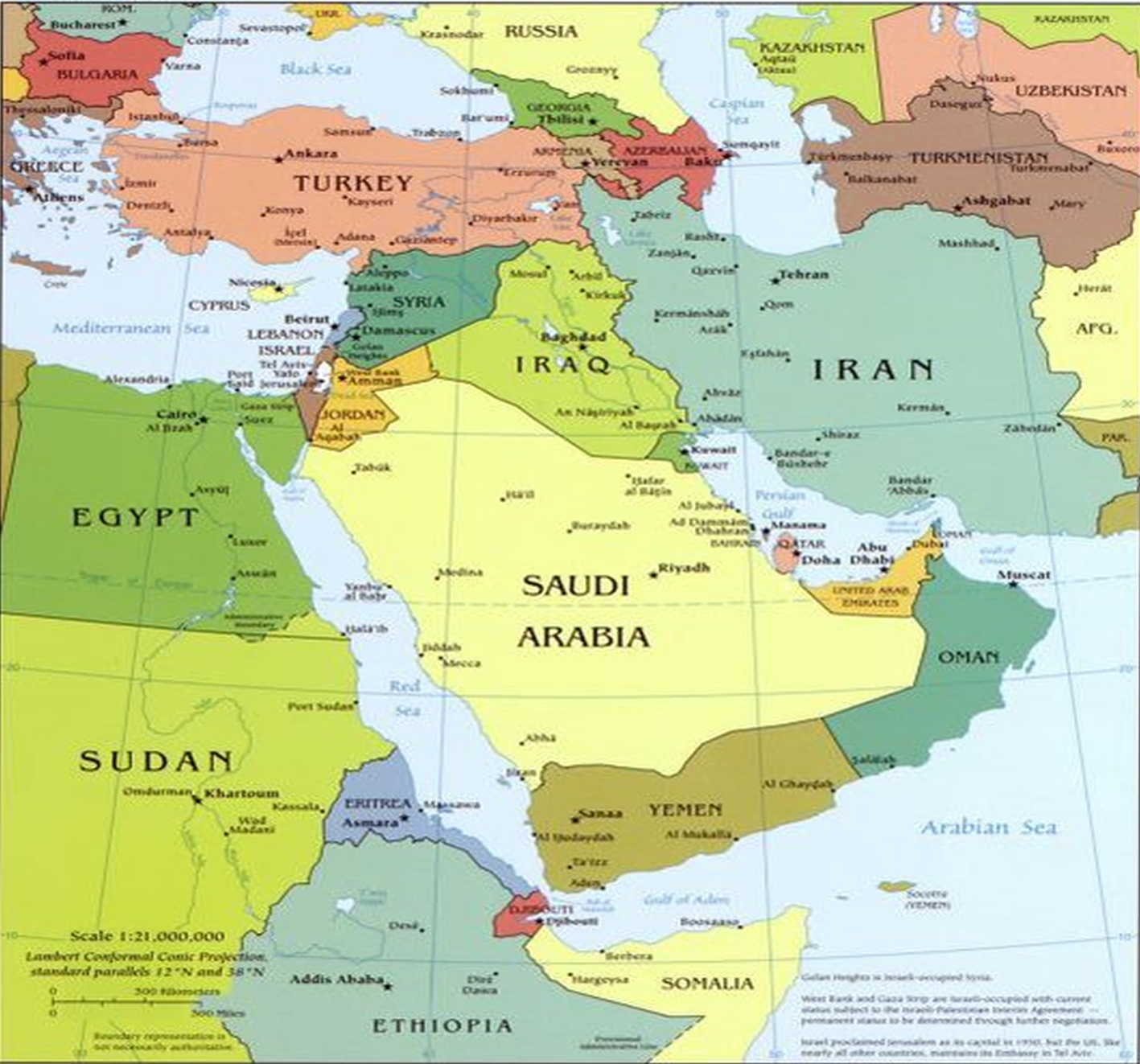

The primarily goal is a protection of Russia’s national security and rising its role as one of major great powers defining the world order. From a Russian security perspective, the Middle East and particularly the Gulf region can be defined as a continuation of the Caucuses region. Thus, major security developments in this region directly influence the security situation in the Caucasus and consequently influence Russia’s national security per se.[3] Therefore, Russia’s presence and influence over the developments in the region are necessary to protect Russia’s national security.

Library of Congress[4]

Second, Russia strives to increase its involvement on the regional markets: predominantly on the arms market; in the non-military nuclear sphere; in the field of food supplies (especially in the Gulf’s Arab countries); infrastructure projects such as railways, oil and gas industry (especially in Iran and Iraq) etc.[5]

Third, Russia strives to attract investments from rich countries of the Gulf. Especially considering the deficiency of foreign investment in Russian economy which deteriorated following Russia’s intervention in Ukraine in 2014 and subsequent imposition of Western sanctions on Russia.[6]

Forth, Russian government strives to influence energy prices (oil and gas) by coordinating price policy with the major energy producers from the Gulf.[7] This is considering significant reliance of the Russian budget on revenues of Russia’s oil and gas sectors.[8] Thus, this factor plays an important role in maintaining the socio-economic well-being of Russia’s society and consequently a stability of the regime.

Consequently, Russia’s leadership utilized different military, political, technological, and economic measures directed at the region’s countries in order to fulfill the mentioned goals. However, the success of these measures can be rather defined as limited.

Overall, Russia succeeded in the formation of a relatively stable military, technological and political connections only with Iran. This happened, to a large extent, due to a shared animosity of Russia and Iran towards the US and the American sanctions imposed on both countries. Consequently, Russia has become Iran's main arms supplier. Over the past ten years, two-thirds of Iranian defense imports came from Russia, while most significant became a US $800 million supply of Russian S-300 air defense systems.[9] Furthermore, Russia expects that following a lifting of the arms sanction against Iran in October 2020, Russia will be able to supply additional complicated weapon systems to Iran.[10]

At the same time, a military presence of Russia in the region remains insignificant. It is remarkable, that Russia, Iran and the PRC conducted a naval exercise in the Northern Part of the Indian Ocean in December 2019. The exercise was designed to demonstrate to the US and the regional countries that the US does not possess a monopoly on military presence in the region, while Russia and the PRC demonstrated readiness to be present in the region, playing a more active role in the formation of a regional security framework and potentially cooperate with Iran under some conditions. However, the size of the exercise and of the involved Chinese and Russian forces were insignificant, and rather symbolic.[11]

Russian involvement in the region in the energy sector, including nuclear energy and infrastructure projects, has had relative success only in Iran. Generally, apart from some commercial benefits, Russia established a meaningful influence over Iran through technology and military supplies, involvement in energy projects in Iran and due to Iranian dependence on Russia in international organizations and Iranian efforts to counteract the effect of US sanctions.[12]

At the same time, Russia’s arms export to the GCC (Gulf Cooperation Council) countries remains relatively limited. Only the United Arab Emirates in the last 25 years purchased Russian weapons for several billion dollars. However, in comparison with purchases from the United States, the arm deals with Russia look insignificant.[13] Also, cooperation in the field of nuclear energy with GCC countries remained limited or mostly on a declarative level.[14]

Overall, Russia succeeded to establish some level of influence only on Iran, while the rest of the countries in the region mostly remained insensitive to Russian efforts. Also, Russia’s economic cooperation with the Gulf countries remains on a relatively low level. Frankly speaking, Russia lacks significant economic resources or technologies (beyond military technologies and some technologies in the nuclear sphere) which could attract GCC countries. While politically, GCC countries do not depend on Russia.

The following table demonstrates[15] a relatively low level of economic cooperation between Russia, the major Gulf countries, and Iran (the Netherlands is presented for comparison).

|

In 2019 |

Iran |

UAE |

Saudi Arabia |

Netherlands (in 2018) |

|

Trade Turnover in the US$ |

1.59 billion |

1.84 billion |

1.67 billion |

47.1 billion |

|

Percentage in Russia’s foreign trade |

0.24% |

0.28% |

0.25% |

6.86% |

|

Importance |

59th |

52th |

57th |

15th |

As can be seen, a trade turnover between Russia and Netherlands in 2018, was almost 30 times bigger than between Russia and Iran in 2019.

Nonetheless, Russia’s leadership strives to advance a strategic dialogue between Russia and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). After all, Russia recognizes the rising role of the Gulf Countries, especially of the UAE, as a global financial center. From the Russian perspective, a ‘strategic dialog’ is an effective mechanism for coordinating efforts in the interests of strengthening regional and global security and stability, thereby expanding economic interaction between Russia and the Arab countries of the Gulf.[16]

Furthermore, Russian leadership strives to assure the Arab countries that Russia’s cooperation with Iran is not directed against them. It is noteworthy that in the framework of the ‘strategic dialog’, Russia condemned an intervention of the Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard into the internal affairs of the Arab countries. Furthermore, the Russian government demonstrates a negative attitude towards a potential acquisition of nuclear weapons by the Iranian regime. At the same time, Russian leadership feels confident that it can mediate between Iran and Saudi Arabia in order to downscale tensions in the Gulf.[17]

Also, in the framework of the ‘strategic dialog’, Russia strives to attract investments from the rich countries of the Gulf and influence energy prices by coordinating policies with major energy producers from the Gulf. Russia also expects to participate in future supplies of Russian weapons (for example S-400) to the Gulf Countries and to participate in different infrastructural and nuclear energy projects.[18]

However, so far Russia’s efforts to coordinate energy prices with the Gulf countries (see oil-price war 2020 between Saudi Arabia and Russia) and efforts to attract significant investments have mostly failed. Also, the Gulf’s countries intentions to purchase Russian arms remain mostly on a declarative level.[19]

At the same time, Russia and the Gulf countries' vision for Syria's future coincides, to some extent.

Russia and the Gulf countries agree that the situation in Syria should be stabilized, while Syria needs reconstruction of its economy and infrastructure. In fact, it will be difficult to sustain a stability in Syria without some reconstruction process. Furthermore, both sides share an interest (not including Qatar) in the weakening of an Iranian and Turkish influence in Syria.[20]

Apparently, Russia alone does not possess the necessary resources for the reconstruction of Syria. Consequently, Russia needs the Gulf countries' resources and influence in order to launch the reconstruction of Syria, while restricting an Iranian influence on this process. This will strengthen a Russian position in Syria and generally in the Middle East. In exchange, Russia may take into consideration the Gulf’s countries security interests in the region. In this way, undermining Iranian and Turkish influence in Syria. In this regard, a cooperation between Russia and the Gulf countries (especially the UAE) in Libya may serve as an example for a possible cooperation in Syria.[21]

At the same time, it can be argued that despite a cooperation between Russia and Iran in different fields (arms supplies, nuclear energy, resistance to American sanctions, infrastructural projects), Russia and Iran have multiplied divergences in many areas, for example, Russia does not share the ideology and aims of the Islamic Revolution.[22] Thus, the Russian-Iranian relationship should be seen rather as a tactical alliance based on specific issues where interests converge, rather than a longer-term strategic partnership reflecting fundamental similarities in the two countries' world views.

Additionally, the Russian government can be interested in cooperating with the Gulf Countries in combating international terrorism, and particularly in neutralizing Islamist groups in the territory of the former Soviet Union. That is, Russia’s government seeks to contain Islamic radicalism which has a strong potential in Russia’s Muslim Republics, especially in the North Caucasus (more than 12-15% of Russia’s native population practices Islam, plus millions of legal and illegal Muslim immigrants from the former Soviet Central Asian Republics) and in Central Asian Countries which directly influence the security situation in Russia.[23]

During the First and Second Chechen Wars militants received significant financial, ideological and manpower support from individuals and some organizations from the Gulf. Therefore, the Russian government prefers to prevent the same scenario in the future. Thus, through cooperation with Gulf countries, Russian authorities strive to prevent funding and ideological support for radical Islamists in the post-Soviet sphere.[24]

At the same time, Russian involvement in the Persian Gulf has a number of restrictions based on Russia’s intrastate features:

Limited economic resources – Russian nominal GDP comprises just 7% of American nominal GDP; [25]

Limited conventional power projection potential;

Structurally weak and ineffective economy with multiply obstacles for modernization undermined by pervasive corruption and luck of new civil technologies; [26]

A very difficult demographic situation; [27]

Consequently, in the long run, all these factors will undermine Russia’s efforts to strengthen its influence in the region.

[1] Graham Thomas. 2019. “Let Russia Be Russia: The Case for a More Pragmatic Approach to Moscow.” Foreign Affairs, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/russia-fsu/2019-10-15/let-russia-be-russia; Radin Andrew, Davis Lynn E., Geist Edward, Han Eugeniu, Massicot Dara, Povlock Matthew , Reach Clint, Boston Scott, Charap Samuel, Mackenzie William, Migacheva Katya, Johnston Trevor, and Long Austin. 2019. RAND. “Research Brief: What Will Russian Military Capabilities Look Like in the Future?”, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB10038.html#:~:text=Russia's%20future%20development%20of%20ground,)%3B%20and%20rapidly%20deployable%20forces; Trenin Dmitri. 2016. “RUSSIA IN THE MIDDLE EAST: MOSCOW’S OBJECTIVES, PRIORITIES, AND POLICY DRIVERS.” Carnegie, https://carnegieendowment.org/files/03-25-16_Trenin_Middle_East_Moscow_clean.pdf

[2] Trenin Dmitri. 2016. “RUSSIA IN THE MIDDLE EAST: MOSCOW’S OBJECTIVES, PRIORITIES, AND POLICY DRIVERS.” Carnegie, https://carnegieendowment.org/files/03-25-16_Trenin_Middle_East_Moscow_clean.pdf

[3] Квашнин Ю., Тоганова Н. 2017. “Большой Ближний Восток в мировой политике и экономике.” Мировое развитие: Выпуск 18. ИМЭМО РАН, https://www.imemo.ru/files/File/ru/publ/2017/2017_026.pdf ; Graham Thomas. 2019. “Let Russia Be Russia: The Case for a More Pragmatic Approach to Moscow.” Foreign Affairs, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/russia-fsu/2019-10-15/let-russia-be-russia; Ханалиев Нурадин. ПРИОРИТЕТЫ НАЦИОНАЛЬНОЙ БЕЗОПАСНОСТИ РОССИИ НА БОЛЬШОМ БЛИЖНЕМ ВОСТОКЕ. Геополитика, https://www.jour.fnisc.ru/upload/journals/2/articles/5404/submission/original/5404-10039-1-SM.pdf; Федорченко А, Крылов А. 2019. “Среднесрочный прогноз развития ситуации в регионе Ближнего Востока и Северной Африки.” БЛИЖНИЙ ВОСТОК В ФОКУСЕ ПОЛИТИЧЕСКОЙ АНАЛИТИКИ. МГИМО, https://mgimo.ru/upload/iblock/d9b/blizhnij-vostok-v-fokuse-politicheskoj-analitiki.pdf;

[4] Middle East. Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2008624818/

[5] Федорченко А. 2019. "БЛИЖНЕВОСТОЧНАЯ ПОЛИТИКА РОССИИ: «Арабская весна» и экономические интересы России." БЛИЖНИЙ ВОСТОК В ФОКУСЕ ПОЛИТИЧЕСКОЙ АНАЛИТИКИ. МГИМО, https://mgimo.ru/upload/iblock/d9b/blizhnij-vostok-v-fokuse-politicheskoj-analitiki.pdf ; Федорченко А. 2019. "Россия – аравийские монархии: потенциал сотрудничества." БЛИЖНИЙ ВОСТОК В ФОКУСЕ ПОЛИТИЧЕСКОЙ АНАЛИТИКИ. МГИМО, https://mgimo.ru/upload/iblock/d9b/blizhnij-vostok-v-fokuse-politicheskoj-analitiki.pdf.

[6] Trenin Dmitri. 2016. “RUSSIA IN THE MIDDLE EAST: MOSCOW’S OBJECTIVES, PRIORITIES, AND POLICY DRIVERS.” Carnegie, https://carnegieendowment.org/files/03-25-16_Trenin_Middle_East_Moscow_clean.pdf; Федорченко А. 2019. "БЛИЖНЕВОСТОЧНАЯ ПОЛИТИКА РОССИИ: «Арабская весна» и экономические интересы России." БЛИЖНИЙ ВОСТОК В ФОКУСЕ ПОЛИТИЧЕСКОЙ АНАЛИТИКИ. МГИМО, https://mgimo.ru/upload/iblock/d9b/blizhnij-vostok-v-fokuse-politicheskoj-analitiki.pdf

[7] “ИНТЕРВЬЮ АЛЕКСАНДРА НОВАКА КУВЕЙТСКОЙ ГАЗЕТЕ «АС-СИЯСА»”. Министерство энергетики Российской Федерации, https://minenergo.gov.ru/node/7516; Trenin Dmitri. 2016. “RUSSIA IN THE MIDDLE EAST: MOSCOW’S OBJECTIVES, PRIORITIES, AND POLICY DRIVERS.” Carnegie, https://carnegieendowment.org/files/03-25-16_Trenin_Middle_East_Moscow_clean.pdf;

[8] Николаев Игорь. 20 December 2020. “Далеко ли до конца иглы? Проверяем слова президента о выходе страны из зависимости от нефти и газа.” Новая газета, https://novayagazeta.ru/articles/2020/12/20/88459-daleko-li-do-kontsa-igly

[9] Russell Martin. 2018. “Russia in the Middle East: From sidelines to centre stage.” European Parliamentary Research Service, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2018/630293/EPRS_BRI(2018)630293_EN.pdf

[10] Trenin Dmitri. 2016. “RUSSIA IN THE MIDDLE EAST: MOSCOW’S OBJECTIVES, PRIORITIES, AND POLICY DRIVERS.” Carnegie, https://carnegieendowment.org/files/03-25-16_Trenin_Middle_East_Moscow_clean.pdf

[11] “Россия, Иран и Китай в ходе учений отработали обеспечение безопасности судоходства.” 15 January 2020. ТАСС, https://tass.ru/politika/7521793

[12] Никольский Алексей. 10 November 2015. “К визиту короля Саудовской Аравии готовят оружейные контракты: Но пока под вопросом и сам визит, и заинтересованность в наших вооружениях.” Ведомости, https://www.vedomosti.ru/politics/articles/2015/11/11/616329-vizitu-korolya-saudovskoi-aravii-gotovyat-oruzheinie-kontrakti; Бирюков Е. 2017. “Некоторые аспекты внешней торговли России с Саудовской Аравией.” Экономика и предпринимательство, № 9 (ч.3), https://mgimo.ru/upload/iblock/d47/50-3%20%D0%91%D0%B8%D1%80%D1%8E%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%B2.pdf; Trenin Dmitri. 2016. “RUSSIA IN THE MIDDLE EAST: MOSCOW’S OBJECTIVES, PRIORITIES, AND POLICY DRIVERS.” Carnegie, https://carnegieendowment.org/files/03-25-16_Trenin_Middle_East_Moscow_clean.pdf; Russell Martin. 2018. “Russia in the Middle East: From sidelines to centre stage.” European Parliamentary Research Service, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2018/630293/EPRS_BRI(2018)630293_EN.pdf

[13] “Trade Registers.” SIPRI, http://armstrade.sipri.org/armstrade/page/trade_register.php; Wezeman Pieter, et al. 2020. “TRENDS IN INTERNATIONAL ARMS TRANSFERS, 2019.” SIPRI, https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2020-03/fs_2003_at_2019.pdf

[14] Сурков Николай. 13 October 2019. “Москва предложит Эр-Рияду ракеты и хлеб: Визит Путина в Саудовскую Аравию – новое продвижение РФ на Ближний Восток.” Независимая газета, https://www.ng.ru/dipkurer/2019-10-13/9_7700_saudy.html

[15] Внешняя Торговля России, https://russian-trade.com/

[16] «Путин выступил за развитие экономических связей России с Саудовской Аравией и ОАЭ.” 13 October 2019. ТАСС, https://tass.ru/politika/6994147; Ramani Samuel. 2020. “Russia and the UAE: An Ideational Partnership.” Middle East Policy, Volume 27(1), https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/mepo.12479; “Межгосударственные отношения России и Объединенных Арабских Эмиратов.” 15 October 2019. РИА Новости, https://ria.ru/20191015/1559754132.html

[17] “Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov’s remarks and answers to media questions at a joint news conference with Saudi Foreign Minister and GCC Chair Adel bin Ahmed Al-Jubeir following the Fourth Ministerial Round of the Russia-GCC Strategic Dialogue.” 26 May 2016. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, https://www.mid.ru/sovet-sotrudnicestva-arabskih-gosudarstv-persidskogo-zaliva-ssagpz-/-/asset_publisher/0vP3hQoCPRg5/content/id/2292674;

[18] Бирюков Е. 2017. “Некоторые аспекты внешней торговли России с Саудовской Аравией.” Экономика и предпринимательство, № 9 (ч.3), https://mgimo.ru/upload/iblock/d47/50-3%20%D0%91%D0%B8%D1%80%D1%8E%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%B2.pdf; “Путин выступил за развитие экономических связей России с Саудовской Аравией и ОАЭ.” 13 October 2019. ТАСС, https://tass.ru/politika/6994147; Сурков Николай. 13 October 2019. “Москва предложит Эр-Рияду ракеты и хлеб: Визит Путина в Саудовскую Аравию – новое продвижение РФ на Ближний Восток.” Независимая газета, https://www.ng.ru/dipkurer/2019-10-13/9_7700_saudy.html

[19] Никольский Алексей. 10 November 2015. “К визиту короля Саудовской Аравии готовят оружейные контракты: Но пока под вопросом и сам визит, и заинтересованность в наших вооружениях.” Ведомости, https://www.vedomosti.ru/politics/articles/2015/11/11/616329-vizitu-korolya-saudovskoi-aravii-gotovyat-oruzheinie-kontrakti; Бирюков Е. 2017. “Некоторые аспекты внешней торговли России с Саудовской Аравией.” Экономика и предпринимательство, № 9 (ч.3), https://mgimo.ru/upload/iblock/d47/50-3%20%D0%91%D0%B8%D1%80%D1%8E%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%B2.pdf; Сурков Николай. 13 October 2019. “Москва предложит Эр-Рияду ракеты и хлеб: Визит Путина в Саудовскую Аравию – новое продвижение РФ на Ближний Восток.” Независимая газета, https://www.ng.ru/dipkurer/2019-10-13/9_7700_saudy.html

[20] Lister Charles. 12September 2019. “Russia, Iran, and the competition to shape Syria’s future .” Middle East Institute, https://www.mei.edu/publications/russia-iran-and-competition-shape-syrias-future; Svetlova Ksenia. 29 June 2020. “In the shadow of new American sanctions, Russia continues to expand its influence in Syria.” Institute for Policy and Strategy, IDC Herzliya, https://www.idc.ac.il/en/research/ips/pages/russia-middleeast/russia-28-6-20.aspx

[21] Ramani Samuel. 2020. “Russia and the UAE: An Ideational Partnership.” Middle East Policy, Volume 27(1), https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/mepo.12479; Субботин Игорь. 24 April 2019. “Саудовская Аравия хочет "отбить" Сирию у Ирана: Эр-Рияд уличили в желании наладить связи с Дамаском.” Независимая газета, https://www.ng.ru/world/2019-04-24/7_7565_syria.html; Ramani Samuel. 31 January 2019. “Russia’s Eye on Syrian Reconstruction.” Carnage, https://carnegieendowment.org/sada/78261

[22] Trenin Dmitri. 2016. “RUSSIA IN THE MIDDLE EAST: MOSCOW’S OBJECTIVES, PRIORITIES, AND POLICY DRIVERS.” Carnegie, https://carnegieendowment.org/files/03-25-16_Trenin_Middle_East_Moscow_clean.pdf

[23] Федорченко А. 2019. “Продолжение «Арабской Революции»: сирийские сценарии.” БЛИЖНИЙ ВОСТОК В ФОКУСЕ ПОЛИТИЧЕСКОЙ АНАЛИТИКИ. МГИМО, https://mgimo.ru/upload/iblock/d9b/blizhnij-vostok-v-fokuse-politicheskoj-analitiki.pdf; Ханалиев Нурадин. ПРИОРИТЕТЫ НАЦИОНАЛЬНОЙ БЕЗОПАСНОСТИ РОССИИ НА БОЛЬШОМ БЛИЖНЕМ ВОСТОКЕ. Геополитика, https://www.jour.fnisc.ru/upload/journals/2/articles/5404/submission/original/5404-10039-1-SM.pdf

[24] Hedenskog Jakob. 2020. “Russia and International Cooperation on Counter-Terrorism: From the Chechen Wars to the Syria Campaign.” FOI, https://www.foi.se/rest-api/report/FOI-R--4916--SE

[25] The World Bank, https://www.worldbank.org/

[26] Transparency International. February 21, 2018. “CORRUPTION PERCEPTIONS INDEX 2017.” https://www.transparency.org/news/feature/corruption_perceptions_index_2017

[27] Aleksashenko Sergey. April 2, 2015. Brookings. “The Russian economy in 2050: Heading to labor-based stagnation.” https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2015/04/02/the-russian-economy-in-2050-heading-for-labor-based-stagnation/